A bill to commute the death sentence for convicted pregnant women to life imprisonment and the reintroduction of the sexual harassment in tertiary institutions are highlights in OrderPaper’s GESI tracker last week

In recent times, there has been debate about the unethical implications of sentencing convicted pregnant women in Nigeria to death. This controversial but necessary bill by the House of Representatives highlights the intersection of criminal justice, human rights, and child welfare, advocating for a compassionate reexamination of how the country handles pregnant death row inmates. The bill titled, “A Bill for an Act to Alter Section 33 of the Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, 1999 to Insert a new subsection which Provides that if a Pregnant Woman is Convicted of an Offence Punishable by Death, the Court Shall Sentence her to Life Imprisonment Instead of Death Sentence (HB. 1409)” seeks to alter the penalties issued to pregnant women who have been convicted of capital crimes, switching from death sentence to life imprisonment. The argument is that pregnant women being sentenced to death not only punishes the mother but the unborn child who has committed no crime, thereby issuing dual punishment.

Pregnant prisoners in Nigeria…

The number of pregnant women convicted of murder has remained low. In 2021, the Nigeria Correctional Service revealed that the number of pregnant inmates was five. Currently, 1,874 females are in prison, but records revealing the number of pregnant inmates remains unavailable. However, these rare cases have garnered significant attention due to the moral dilemmas it presents.

What the law Says

It is worth noting that Section 404 and 415(4) of the Administration of Criminal Justice Act (ACJA) expressly provides that “where a woman found guilty of a capital offense is pregnant, the sentence of death shall be passed on her but it shall be suspended until the child is delivered and weaned.”

Furthermore, Section 221(2) and (3) of the Child’s Rights Act which has been domesticated in all states in Nigeria further states that “no expectant mother or nursing mother shall be subjected to the death penalty or have the death penalty recorded against her,” and “a court shall, on sentencing an expectant or a nursing mother, consider the imposition of a non‐institutional sentence as an alternative measure to imprisonment”.

Section 319 of the Criminal Code, which makes provision for pregnant women, states that “where a woman who has been convicted of murder alleges she is pregnant or where the judge before whom she is convicted considers it advisable to have inquiries made as to whether or not she be pregnant, the procedure laid down in section 376 of the Criminal Procedure Act shall first be complied with.”

While the ACJA supports the sentencing to death of the pregnant woman with a clause of suspending the sentence until she delivers and weans the child, the Child Rights Act and the Criminal Code Act makes other provisions for the pregnant woman. The need to harmonize these laws is crucial not just for the pregnant woman but for the unborn child as well to ensure social inclusion.

GESI implications in the bill

GESI frameworks aim to address systemic inequalities and ensure that all individuals, regardless of gender, social status, or other identity factors, are treated equitably. Therefore, this bill prompts a wider reflection on gender-specific issues within the criminal justice system as it serves as a reminder that women, especially those who are pregnant, encounter unique challenges and vulnerabilities that the legal system must address with greater sensitivity and awareness.

Compared to their male counterpart, women face different social expectations; however sentencing pregnant women to death can disproportionately affect them due to these unique gender roles, making it a gender-sensitive concern. Furthermore, pregnant women are a vulnerable group, lacking access to social and legal resources, and addressing the sentencing of pregnant women from a GESI perspective ensures that these vulnerable populations receive fairer treatment and better support within the legal system acknowledging their vulnerability

Sentencing pregnant women to death doesn’t just affect the women but also their unborn children; however, changing the sentence to life imprisonment can protect the rights of the child and provide a more stable environment for them, advocating for their social inclusion.

In conclusion, the bill to change the penalty for pregnant women convicted of death to life imprisonment is a humane approach to justice, balancing the severity of the crime with the rights and welfare of innocent children.

Sexual Harassment in Tertiary Institutions

The status of sexual harassment in tertiary institutions in Nigeria has remained a concern that has garnered increasing attention. Despite legislative frameworks aimed at addressing this issue, sexual harassment remains prevalent, affecting the educational experiences for students, particularly women and other vulnerable groups.

Many students have reported experiencing harassment from peers, faculty members, and other institutional staff, however, these reports have not been paid adequate attention. The hierarchical structure has continued to create power imbalances, where faculty and staff use power over students. Furthermore, while many institutions have sexual harassment policies, these policies are not effectively implemented or enforced.

In the bid to address this menace, the 8th Assembly in 2016, introduced the “Prevention, Prohibition, and Redressal of Sexual Harassment in Tertiary Institutions Bill” but the debates on the bill was unconcluded which led to its reintroduction in the 9th Assembly in 2019, which was passed. However, the 9th Assembly failed to transmit the bill to the President which has made the 10th Assembly to reintroduce the bill afresh.

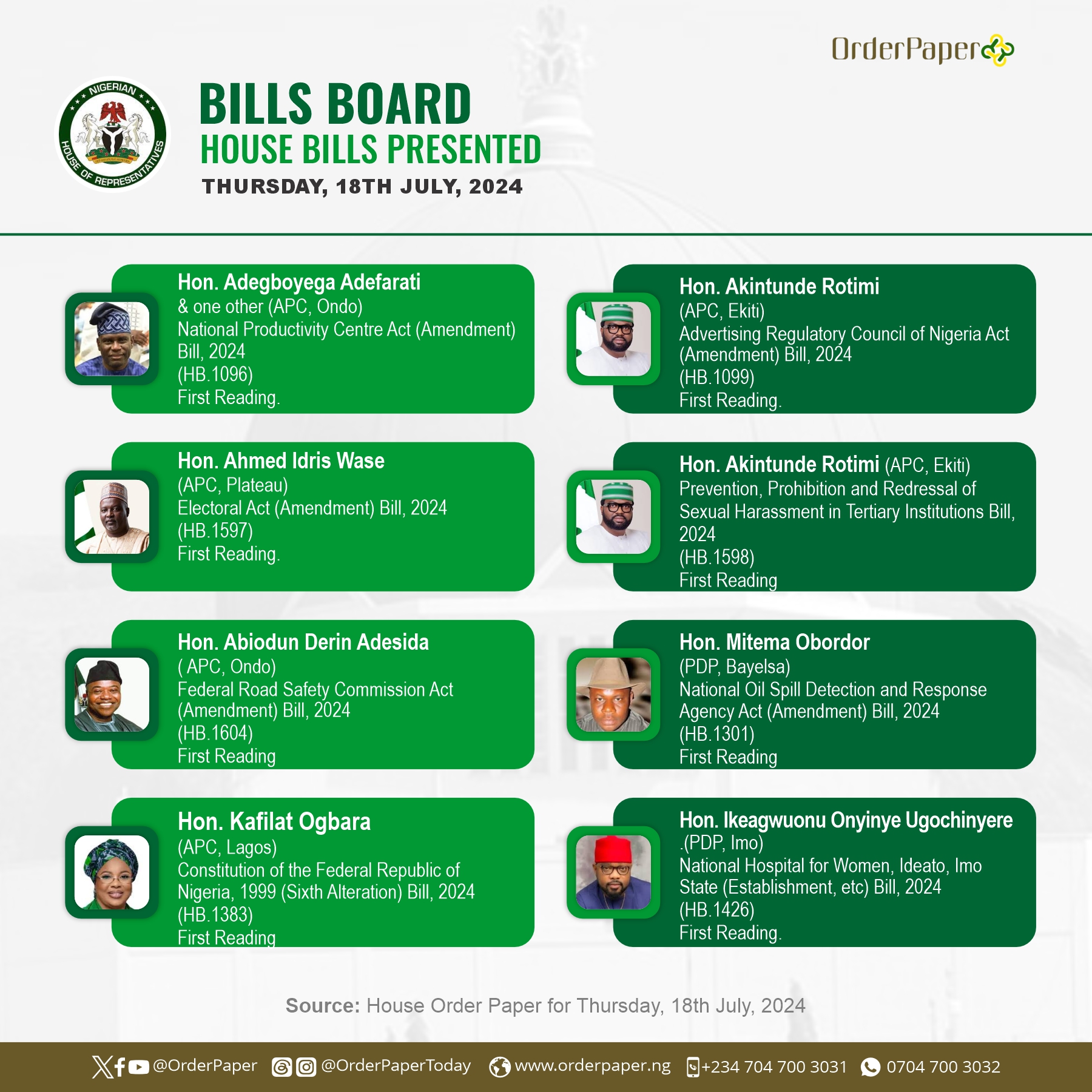

This move is crucial to addressing the issue and ensuring accountability. The bill aims to address the pervasive issue of sexual harassment in educational institutions thereby establishing a safe and conducive learning environment for students, particularly women and other vulnerable groups. Last week at Plenary, Rep. Akintunde Rotimi reintroduced the “Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal of Sexual Harassment in Tertiary Institution Bill” 2024 in the House of Representatives and it has passed the first reading.

Social Inclusion Concerns Raised on Karu Market Fire

The move by the Senate President, Godswill Akpabio, to counter a motion raised by Senator Ireti Kingibe for rebuilding the Karu market and give back the market to the people at affordable and subsidized price after the fire outbreak raises concern as this illustrates a broader trend where the voices of marginalized groups are often sidelined in political discourse. This incident highlights significant issues about social inclusion in the decision-making processes that affect local communities, especially given that markets often serve as vital economic hubs for women and marginalized groups. Akpabio‘s decision raises questions about the government’s commitment to supporting its citizens in times of need.

However, in this context, social inclusion is paramount in ensuring that the needs of all community members particularly those directly affected by crises are taken into account, as ignoring these voices not only perpetuates systemic inequalities, and social exclusion but can also hinder the effectiveness of rebuilding efforts. The rebuilding of the market not only presents an opportunity to restore infrastructure but also pave the way for a more equitable and inclusive economic landscape.

Akpabio’s Derogatory words to Natasha

Senator Akpabio‘s shushing of Sen. Natasha Akpoti-Uduaghan, saying that the Senate is not a night club, is a reflection of underlying gender biases in political discourse which hinders the progress of GESI initiatives. Firstly, using such a statement in the Senate trivializes the seriousness of legislative discussions as comparing the Senate to a nightclub is wrong and undermines the professional nature of governance. It further demonstrates a lack of respect for female colleagues, insinuating that their contributions are not taken seriously. Secondly, the comment reflects the dismissive attitude often directed towards women in male-dominated spaces, suggesting that Akpabio may not fully recognize or respect his Natasha‘s authority and presence in the Senate. This action perpetuates a culture where women’s voices are marginalized and reinforces the idea that women should be subordinate to men, which contradicts GESI principles.