From Bobrisky to the “Queen of Africa” and the reoccurring arrest of gay suspects, it’s been ten years since the enactment of Nigeria’s Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Law. On the GESI Tracker this week, we delve into one of the most controversial laws in recent times, considering its composition, implementation, and criticisms in the past decade and what all these mean for the LGBTQ+ community.

On January 7, 2024, the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) bill, commonly referred to as the “Anti-Gay Act,” was signed into law by former President Goodluck Ebele Jonathan amidst significant controversy and international criticism.

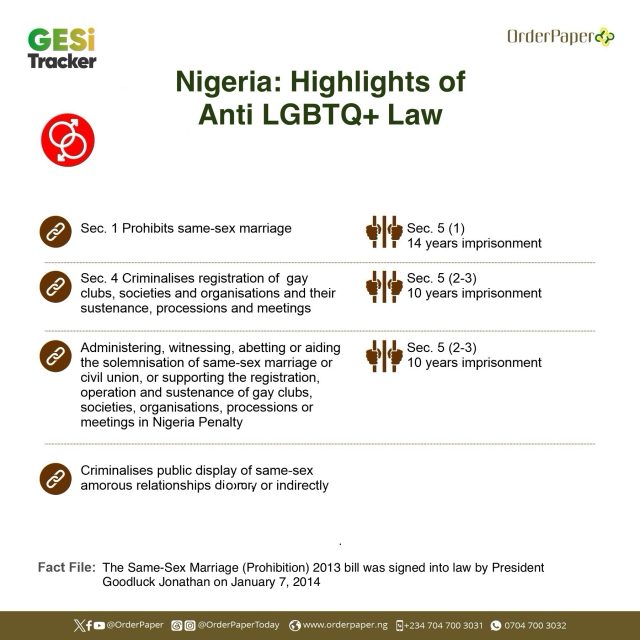

The Act forbids and penalises any marriage or civil union between individuals of the same gender and the celebration of such unions. Additionally, it makes it illegal to register gay clubs, societies, or organisations and prohibits their existence, activities, and gatherings.

Ten years later, what has been the level of implementation, loopholes and backlash or praises faced by the Act?

Reasons for Enactment and Key Provisions of the Anti-Gay Law

The Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act (SSMPA) was crafted in response to mounting calls for marriage equality and the acknowledgement of various consensual sexual relationships. These appeals originated from diverse communities, prominently represented by the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer plus (LGBTQ+ – the plus holds space for the expanding and new understanding of different parts of the very diverse gender and sexual identities.) groups, reflecting the increasing recognition of diverse gender and sexual orientations worldwide.

In 2006, the Same-Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Bill was first introduced to the National Assembly and met a series of opposition from regional and international human rights organisations. The primary fear envisaged by the introduction of the Bill was that it would bring about arbitrariness and discrimination against the LGBTQ+ population. However, in the 7th Assembly, the Bill sponsored by Senator Domingo Obende, representative of Edo North senatorial district, finally gained presidential assent.

READ ALSO: Lagos-Calabar coastal highway: Reps summon Umahi, Edun, AGF

Legal Implications of the Act

The Act provides that “A person who registers, operates or participates in gay clubs, societies or organisations, or directly or indirectly makes public show of same-sex amorous relationship in Nigeria commits an offence and is liable on conviction to a term of 10 years.” Under the Act, individuals who enter into a same-sex marriage or civil union can face imprisonment for up to 14 years. Public displays of affection by same-sex couples can lead to imprisonment for up to 10 years. The Act also imposes penalties on anyone who operates, participates in or supports gay clubs, societies, and organisations. Subsection 2 of section 4 mainly prohibits public show of same-sex amorous relationships. The term ‘amorous’ has been defined as showing sexual desire and love towards any person. It is important to note that the Act does not distinguish between a Nigerian and a non-Nigerian in the context of its application.

Criminalisation of Same-sex Practice in Nigeria and Domestication of the Act

Multiple statutes criminalise same-sex practice in Nigeria, and most States, particularly in the northern part of the country, have laws prohibiting LGBTQ+ persons. Therefore, enacting the SSMPA strengthened other legislations, such as the Penal Code, the Criminal Code Act and extant Sharia laws, particularly in the Northern region. The Criminal code is considered an integral part of the Nigerian legal system. It regulates human criminal conduct by identifying actions that are regarded as crimes.

For example, 12 Northern states have criminalised LGBTQ+ practice with harsh penalties for the offenders. We have the Kaduna State law in Section 125, which provides for the death penalty for offenders. The Zamfara State Sharia Penal Code Law also administers the death penalty, but only where the offenders are married. There is also the Bauchi State law, the Jigawa, and Kano State laws, which all criminalise and penalise acts of sodomisation.

Implementation Thus Far: Witch Hunt or Criminal Offence?

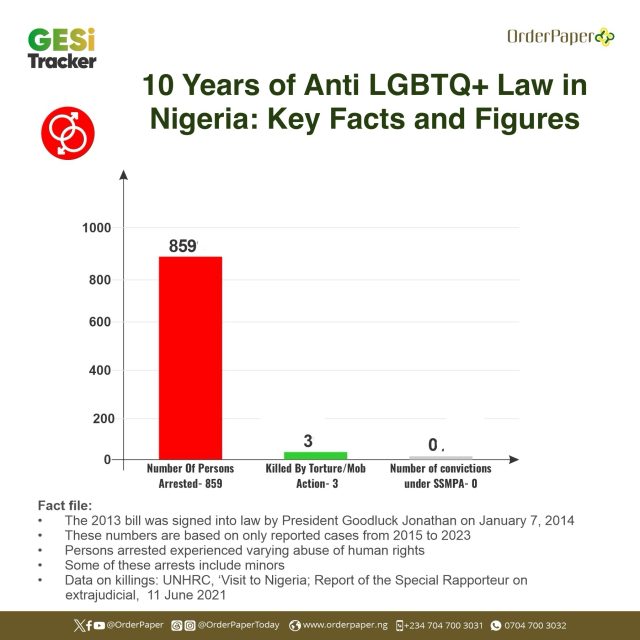

While several arrests have been made under the Act, no known sentences or penalties have been imposed under the Act. Perhaps this is often a result of the lack of evidence to prove them guilty.

The police used the law for the first time in 2019 to prosecute 47 men accused of same-sex public displays of affection in Lagos State. It is worth noting that while arrests have been made as far back as 2015, this was the first known case charged to court. A court dismissed the case because the police failed to appear and present witnesses. James Brown, a crossdresser who refers to himself as the “princess of Africa,” was amongst those arrested.

Similarly, in December 2022, the religious police force, which is popularly known as the Hisbah, enforced its strict moral code with the arrest of 19 persons at yet another gathering tagged a “gay party.”

In another case, on August 30, 2023, the Delta State commissioner of police, Wale Abbas, in a media statement, said 67 men and women were arrested at a hotel in Warri for conducting and attending the purported gay wedding, which is prohibited under Nigeria’s Same Sex Marriage Prohibition Act. The police live-streamed the media spectacle on their official Delta State Police Facebook page.

Another arrest took place in Gombe in October 2023, where more than 70 young people – 59 men and 17 women were accused of “holding homosexual birthdays” and having “the intention to hold a same-sex marriage. These arrests and parading of alleged LGBTQ are a few out of several carried out in the past ten years.

READ ALSO: Senate set to commence full implementation of Disability Act\

The law does not support the police parade of suspects. In 2022, Nigeria’s Federal High Court found that pretrial media parades violate the country’s constitution and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, guaranteeing respect for a person’s dignity and the right to a fair trial, including the presumption of innocence. Despite this ruling, police have continued the abusive practice, which has led to the question of whether the arrests are an act of witch hunt or genuinely investigated cases.

On April 4 2024, a popular crossdresser, Okuneye Idris Olanrewaju, popularly known as Bobrisky, was arrested on Wednesday evening by personnel of the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission (EFCC) in Lagos State. The reason for his arrest was for the alleged abuse of naira notes. This case was interesting because, despite the prohibition against defacing the naira, it is still common practice to see Nigerians spray cash at events without consequences. Hence, the arrest of Bobrisky by the EFCC raised eyebrows as to whether it was really due to the offence of defacing the naira or his identification as female and being a crossdresser, an offence not covered in the SSMPA.

Amendment to the SSMPA

In April 2022, The House of Representatives introduced a bill prohibiting cross-dressing with an amendment to the SSMPA. Muda Umar (Toro Federal Constituency, Bauchi) sponsored the amendment, which sought to amend sections 4 and 5 of the Act to the effect that it would be an offence where cross-dressing is publicly published or displayed publicly, notwithstanding that it was committed privately or in a place that would have ordinarily been described as private and a punishment of imprisonment of 6 months or a fine of five hundred thousand naira.

The spread of anti-gay laws across Africa

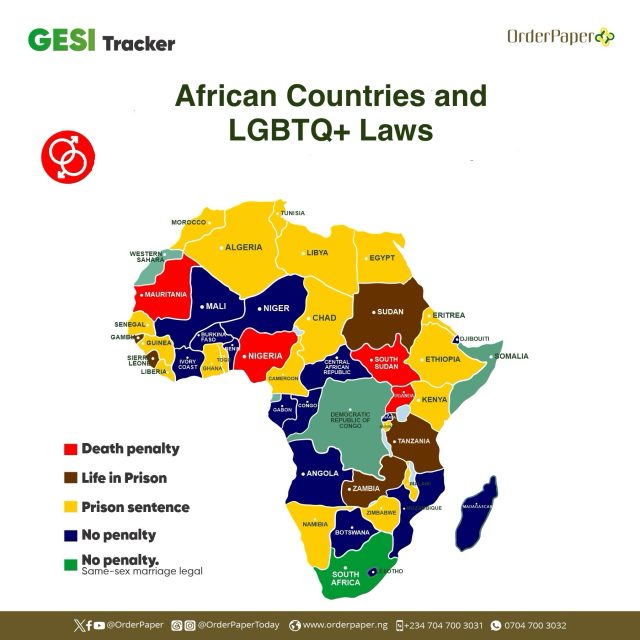

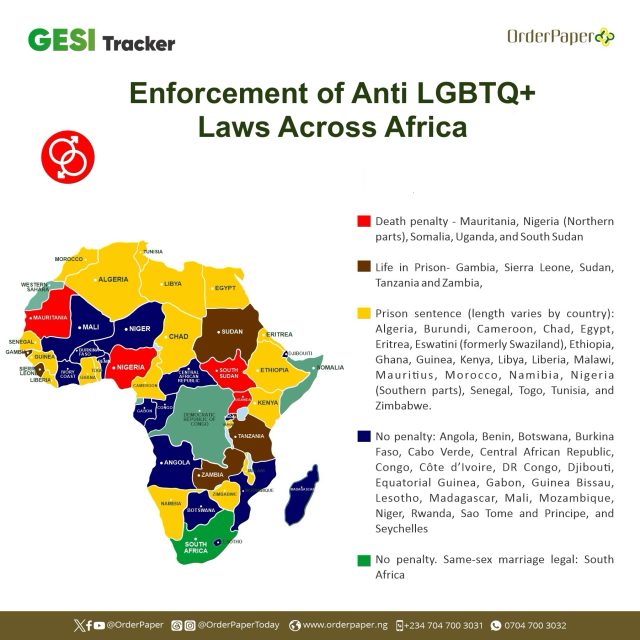

While countries like South Africa, Lesotho, Seychelles, Angola, and Mauritius have taken steps to decriminalise same-sex relationships, the majority of African nations maintain laws that disapprove of LGBTQ+ activities. Among the 54 African states, only 22 have legalised homosexuality, with many others enforcing punitive measures, including imprisonment.

In some countries, such as Mauritania, Nigeria (in states where Sharia law is applied), Somalia, Uganda, and South Sudan, engaging in same-sex relationships can result in the death penalty. This outright prohibition and harsh punishments for LGBTQ+ unions and activities are increasingly prevalent across the continent.

For instance, in March 2023, Uganda reportedly became the first African country to criminalise merely identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or queer (LGBTQ+). Meanwhile, in Kenya, a Supreme Court ruling in February 2023 upheld lower court decisions that the government could not lawfully reject the registration of an organisation called the National Gay and Lesbian Human Rights Commission (NGLHRC). However, President William Ruto, along with many religious leaders and political pundits, condemned the interpretation of the constitution, which prohibited discrimination based on sexual orientation.

Similarly, Ghana’s parliament passed a bill into law earlier this year imposing a prison sentence of up to three years for anyone convicted of identifying as LGBTQ+. In Malawi, same-sex relationships are punishable by up to 14 years in prison under Malawi’sPenal Code. In 2016, the government announced a moratorium on anti-gay laws, but the legal situation remains precarious, with LGBTQ+ individuals facing societal discrimination and occasional arrests.

Also, in 2018, Tanzania intensified its crackdown on LGBTQ+ rights, with authorities announcing the suspension of HIV/AIDS prevention programs targeting gay men. Additionally, individuals suspected of being homosexual have faced arrests, harassment, and forced anal examinations, despite international condemnation.

These developments highlight a trend towards greater intolerance and legal repression of LGBTQ+ individuals and organisations across various African nations.

Criticisms and Human Rights Contradictions within the Act

Critics of the SSMPA have raised questions about its constitutionality. They argue that if genetic factors determine homosexuality, then it should be protected under the provision for “circumstances of birth” in section 42(2) of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended).

It has also been argued that the LGBTQ+ community assert their legitimacy within the framework of privacy rights, a fundamental aspect of human rights outlined in various international documents such as the United Nations Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, and numerous other global and regional instruments which Nigeria has domesticated. The right to privacy encompasses a range of essential rights, including the privacy of individuals, their residences, correspondence, telephone conversations, and telegraphic communications. It is regarded as one of the paramount human rights issues of the contemporary era.

The alleged infringement of human rights through arrests and prosecutions has been a growing concern, attracting criticism from different quarters. It has likewise had an impact on healthcare and HIV/AIDS prevention programmes in Nigeria, as reported by the Guttmacher Institute. This has resulted in the discrimination and persecution that drives many LGBTQ+ individuals underground, making it difficult for them to access essential healthcare services and threats to projects that fund.

Another legal issue arising from the SSMPA is the non-recognition of same-sex marriages contracted outside Nigeria. The Marriage Act, however, recognises marriage contracted outside Nigeria. Hence, an interesting angle to this would be how the Nigerian government navigates diplomats in same-sex marriages sent in by a foreign country where same-sex marriage is legal. Considering the provisions of Section 1(2) of the SSMPA, such people cannot be accredited in Nigeria. The question then arises as to the implementation of the law and the possibility of sparking a diplomatic row.

Moreover, the SSMPA fails to address a fundamental inquiry regarding the definition of “whether an individual is classified as male or female.” This omission creates ambiguity regarding the legal status of intersex individuals, complicating the determination of whether same-sex relationships fall within the scope of prohibited conduct. These unresolved legal queries underscore the complexities surrounding the passage of the SSMPA and its implications on human rights.

READ ALSO: Unravelling the Naira Abuse Scandal

Moral and religious grounds for support of the Act

The Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act in Nigeria has garnered significant moral and religious support, primarily from conservative sectors of society. Many religious leaders, particularly within Christian and Muslim communities, have voiced their backing for the Act, citing religious teachings that uphold traditional family structures and oppose same-sex relationships. These supporters often argue that same-sex marriage contradicts their moral values and religious beliefs, viewing it as a deviation from natural and ordained forms of partnership. They perceive the Act as a means of safeguarding societal norms and moral standards, reinforcing the sanctity of heterosexual marriage as ordained by their faiths. Additionally, proponents of the Act frequently assert that it aligns with Nigeria’scultural and religious heritage, reflecting the collective moral conscience of the nation. This ethical and religious backing has been instrumental in shaping public opinion and sustaining political support for the legislation.

Conclusion:

Over the past ten years, the implementation of the law has led to increased persecution, discrimination, and violence against LGBTQ+ individuals. Despite these challenges, activists and allies continue to push for the repeal of the law and the protection of LGBTQ+ rights in Nigeria. On the other hand, as a country rooted in morality and religion, repealing the law could be seen as an insult to what is morally and spiritually right. However, one thing is evident from the plethora of cases and loopholes. The same-sex marriage (prohibition) Act requires a review.